4.8: Some Economics of Covid-19

ECON 410 · Public Economics · Spring 2020

Ryan Safner

Assistant Professor of Economics

safner@hood.edu

ryansafner/publics20

publicS20.classes.ryansafner.com

Price Gouging

Price Gouging

Where did all of the ... go?

- Toilet paper

- Hand sanitizer

- Masks

- PPE

- Ventilators

Two issues:

- price gouging laws

- supply-side restrictions

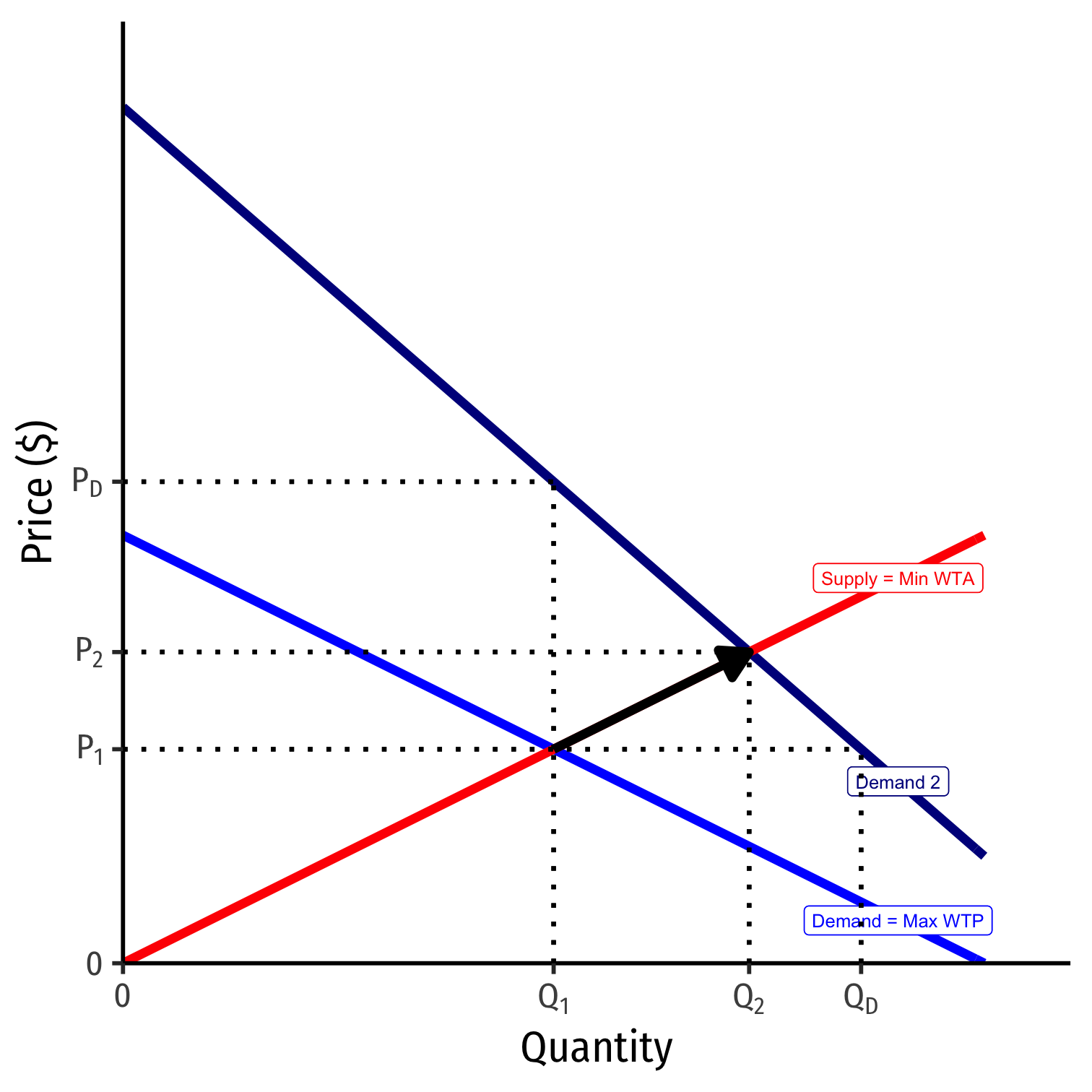

Increase in Demand

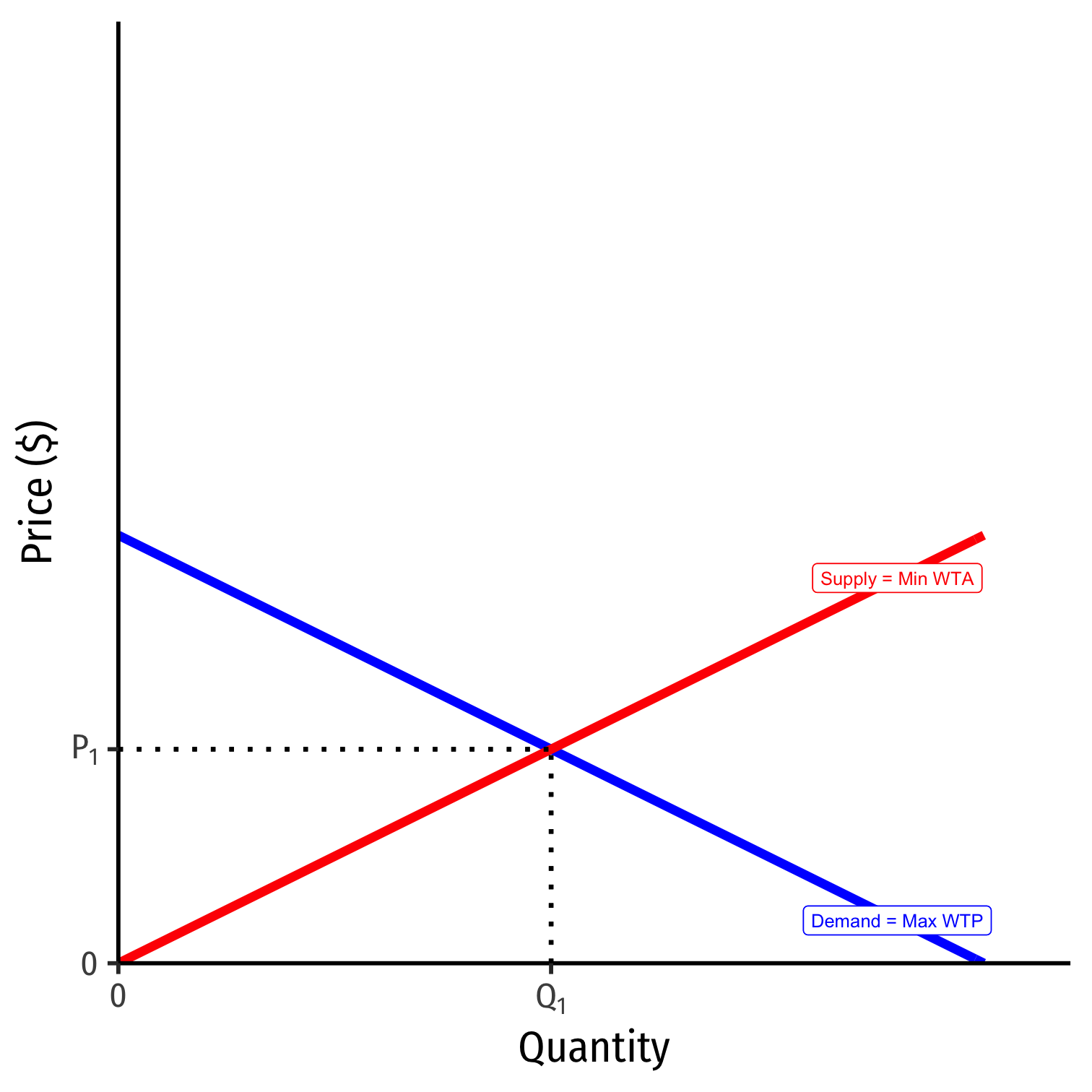

- Consider a market for a good in equilibrium, P1

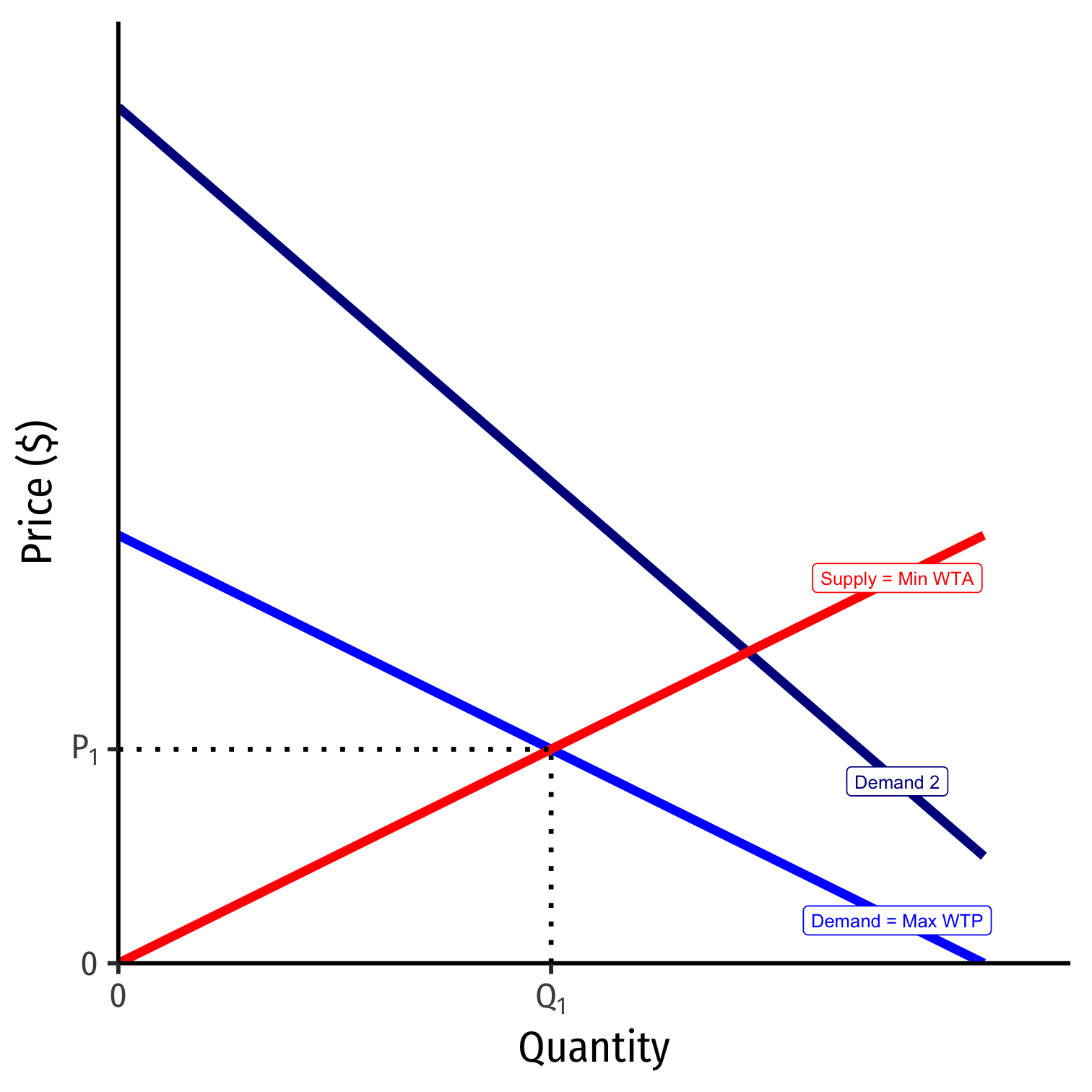

Increase in Demand

More individuals want to buy more of the good at every price

Entire demand curve shifts to the right, becomes less elastic

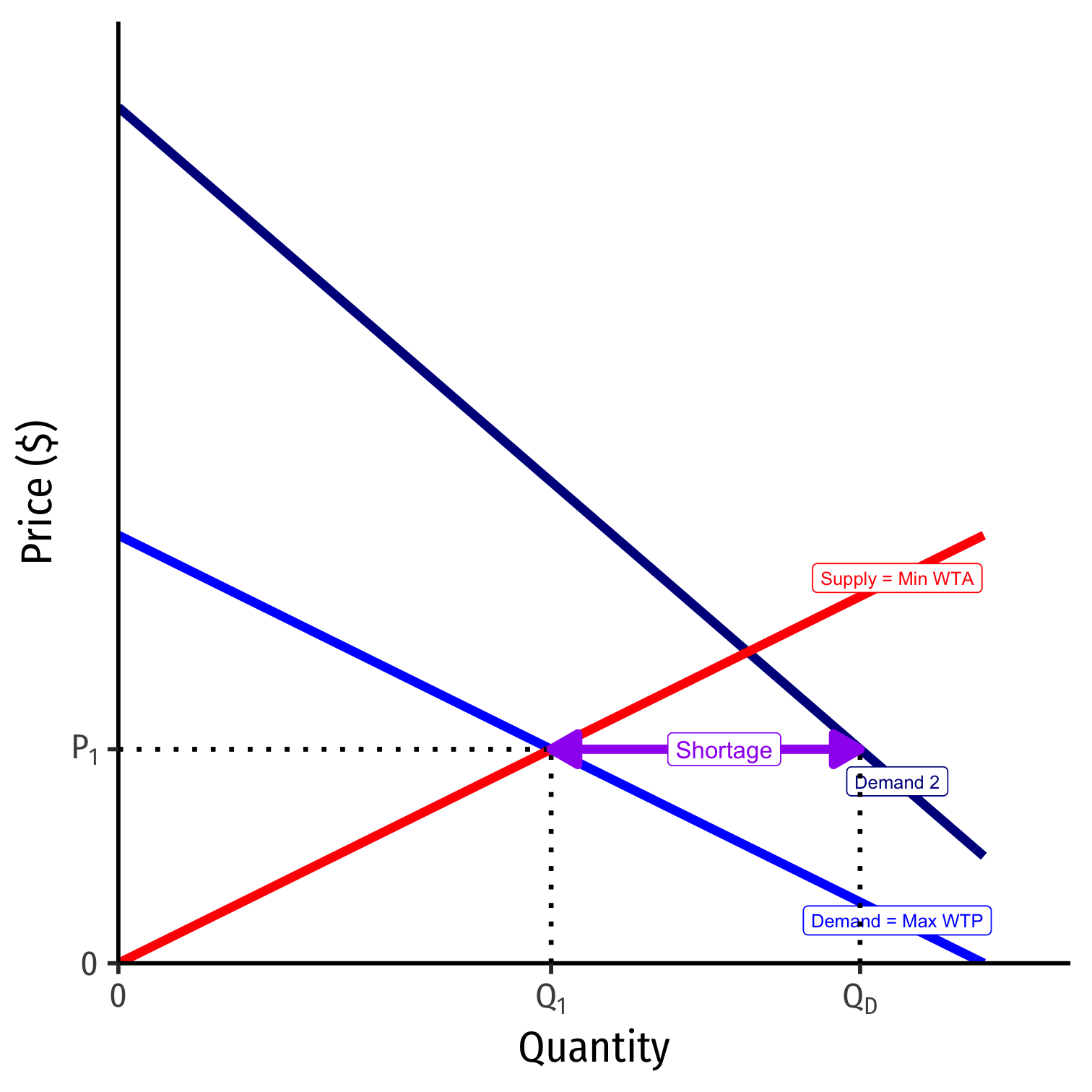

Increase in Demand

More individuals want to buy more of the good at every price

Entire demand curve shifts to the right, becomes less elastic

At the original market price, a shortage! (qD>qS)

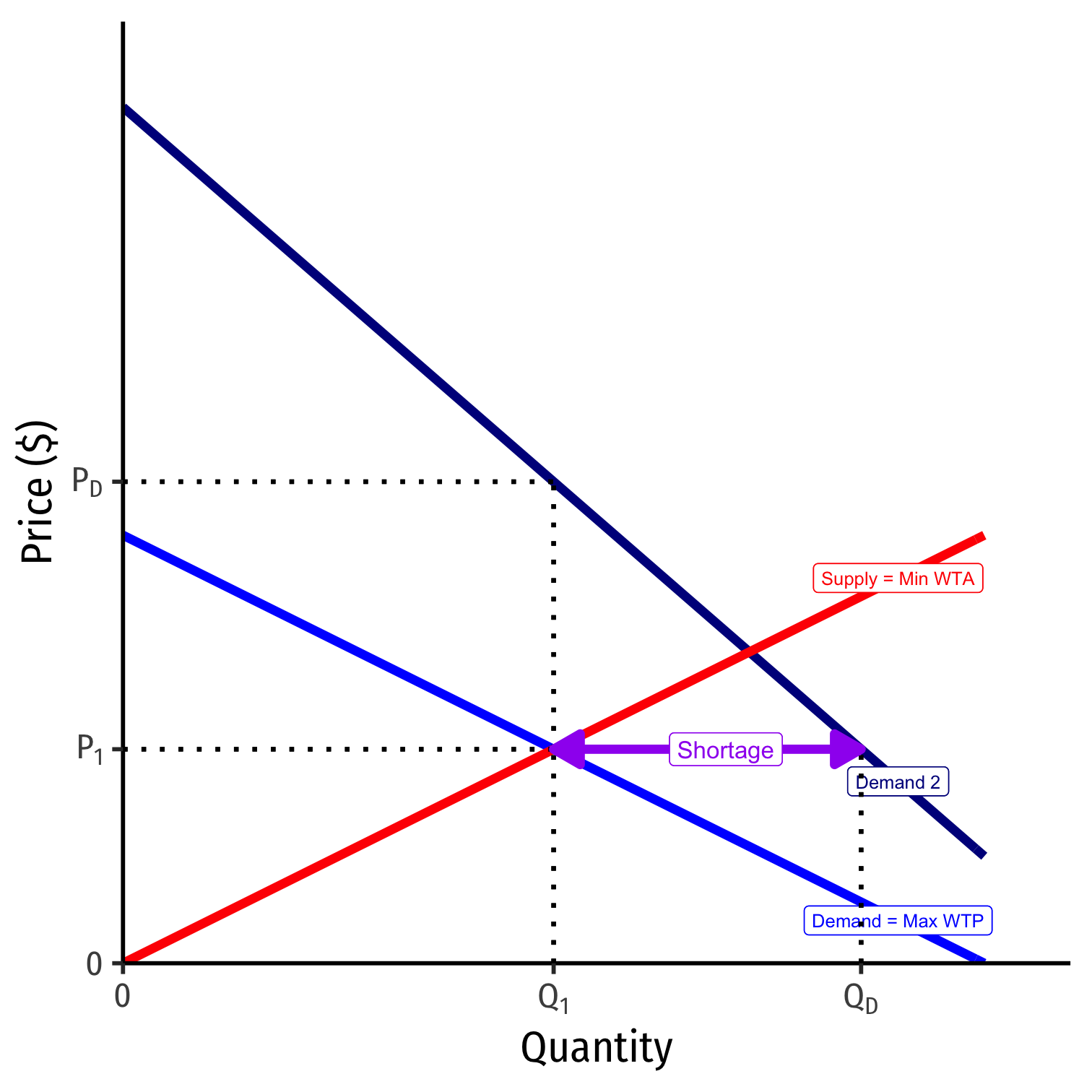

Increase in Demand

More individuals want to buy more of the good at every price

Entire demand curve shifts to the right, becomes less elastic

At the original market price, a shortage! (qD>qS)

Sellers are supplying Q1, but some buyers willing to pay more for Q1

Increase in Demand

More individuals want to buy more of the good at every price

Entire demand curve shifts to the right, becomes less elastic

At the original market price, a shortage! (qD>qS)

Sellers are supplying Q1, but some buyers willing to pay more for Q1

Buyers raise bids, inducing sellers to sell more

Reach new equilibrium with:

- higher market-clearing price (P2)

- larger market-clearing quantity exchanged (Q2)

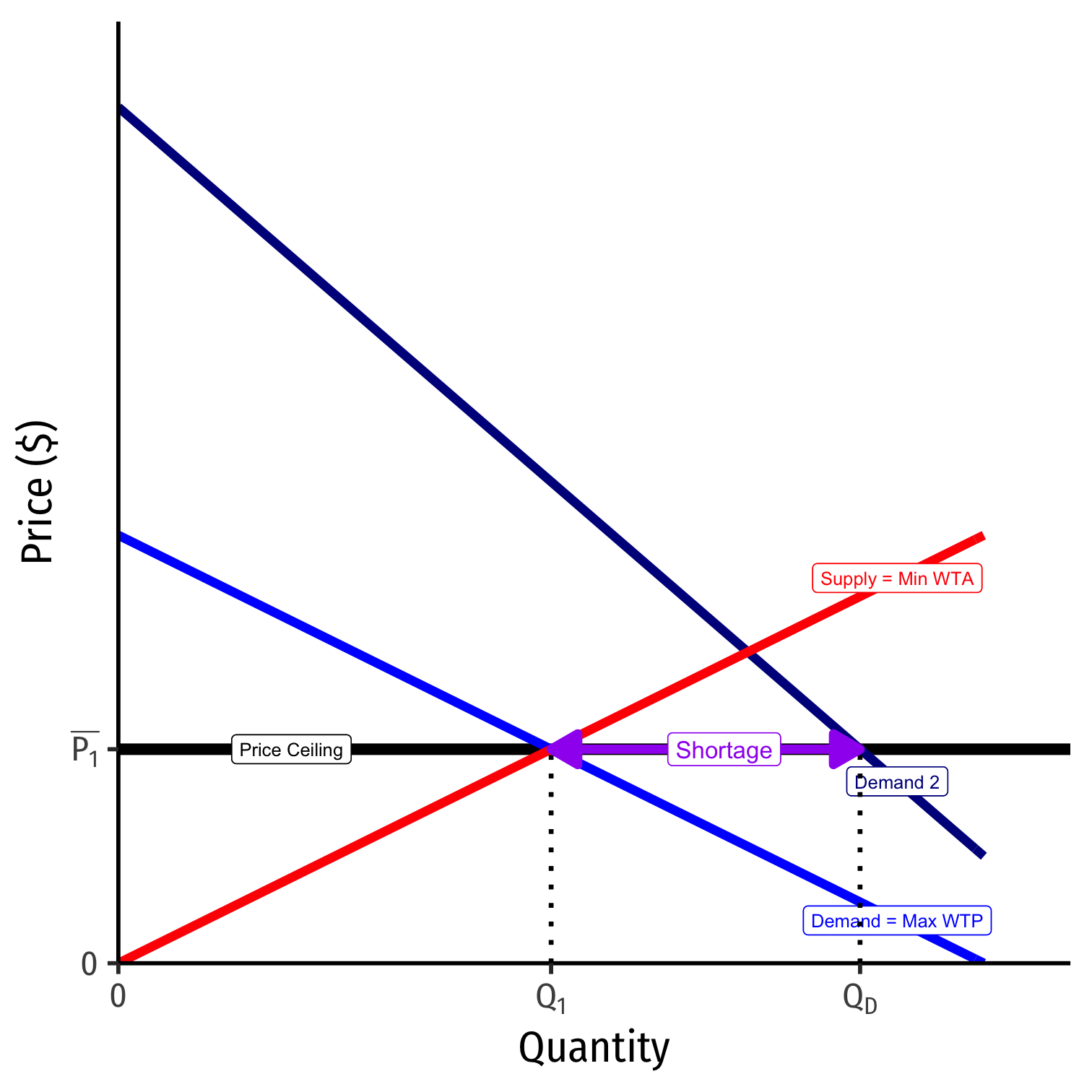

Price Gouging Laws

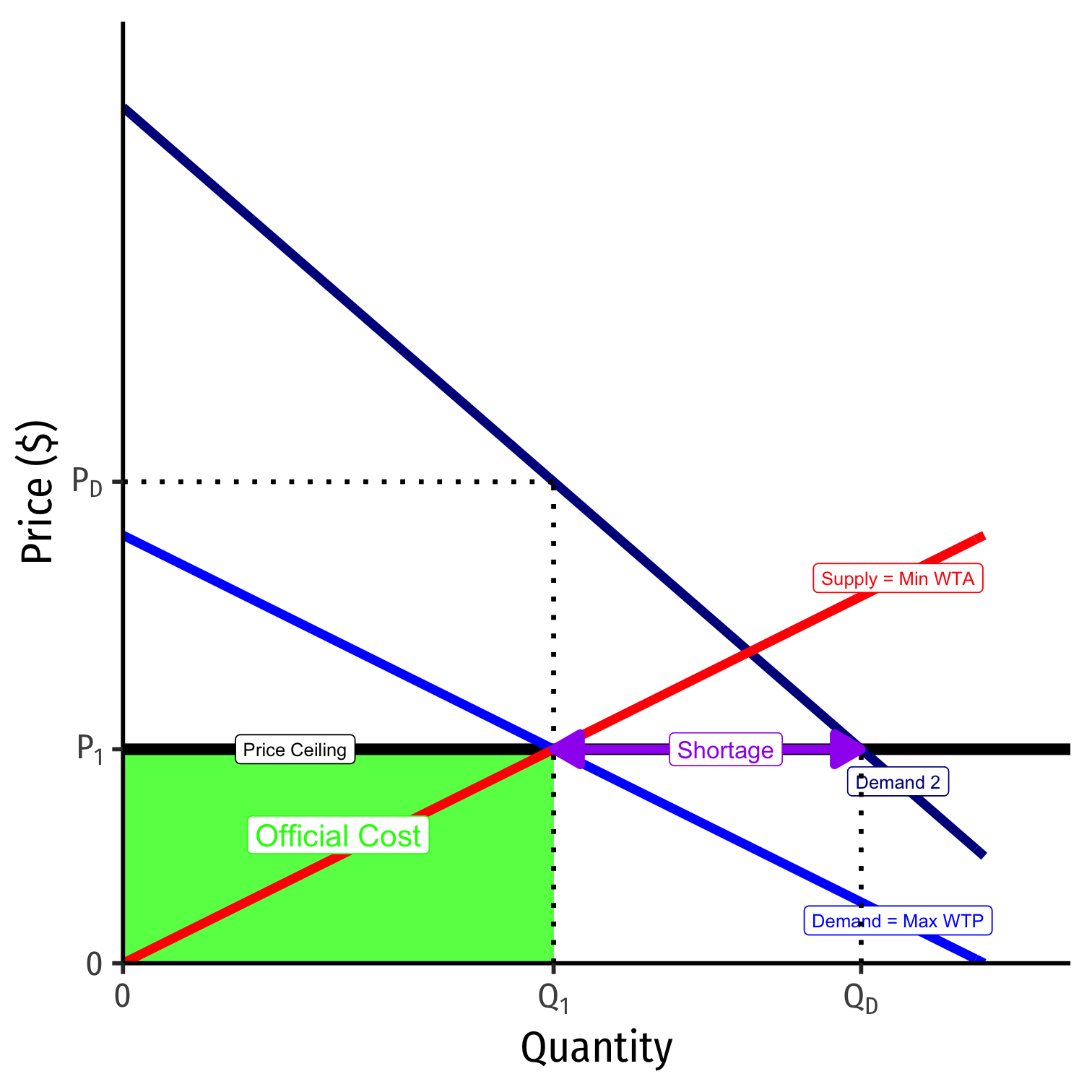

Suppose instead, government has price gouging laws, a price ceiling at the original price, P1

Qd>Qs: excess demand, a shortage!

Sellers will not supply more than Q1 at price ¯P1

Price Gouging Laws

Suppose instead, government has price gouging laws, a price ceiling at the original price, P1

Qd>Qs: excess demand, a shortage!

Sellers will not supply more than Q1 at price ¯P1

For Q1 units, buyers are willing to pay PD!

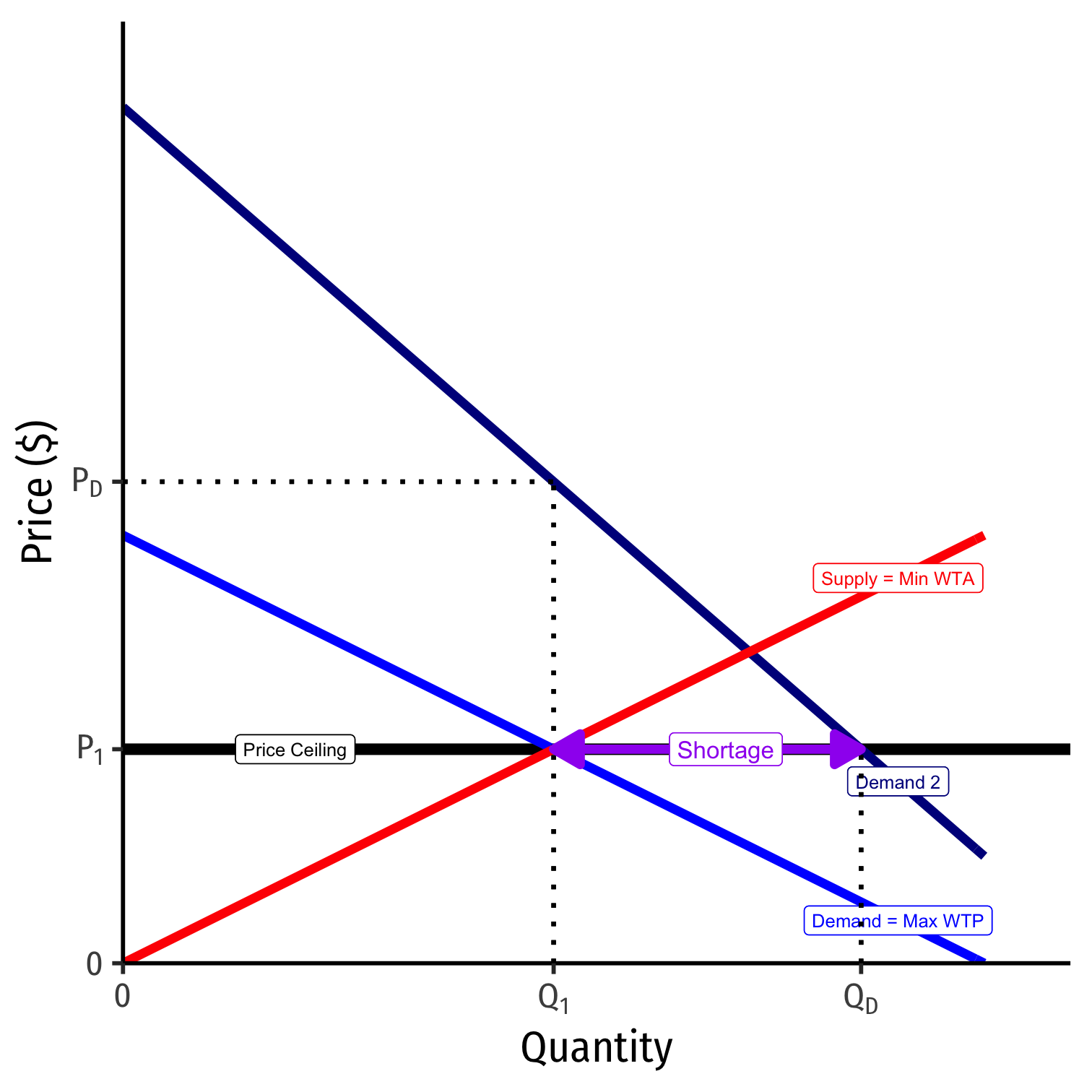

Price Gouging Laws

If prices were allowed to adjust: buyers would bid higher prices to get the scarce Qs goods

Sellers would respond to rising willingness to pay, and produce and sell more

But the price is not allowed to rise above ¯P1!

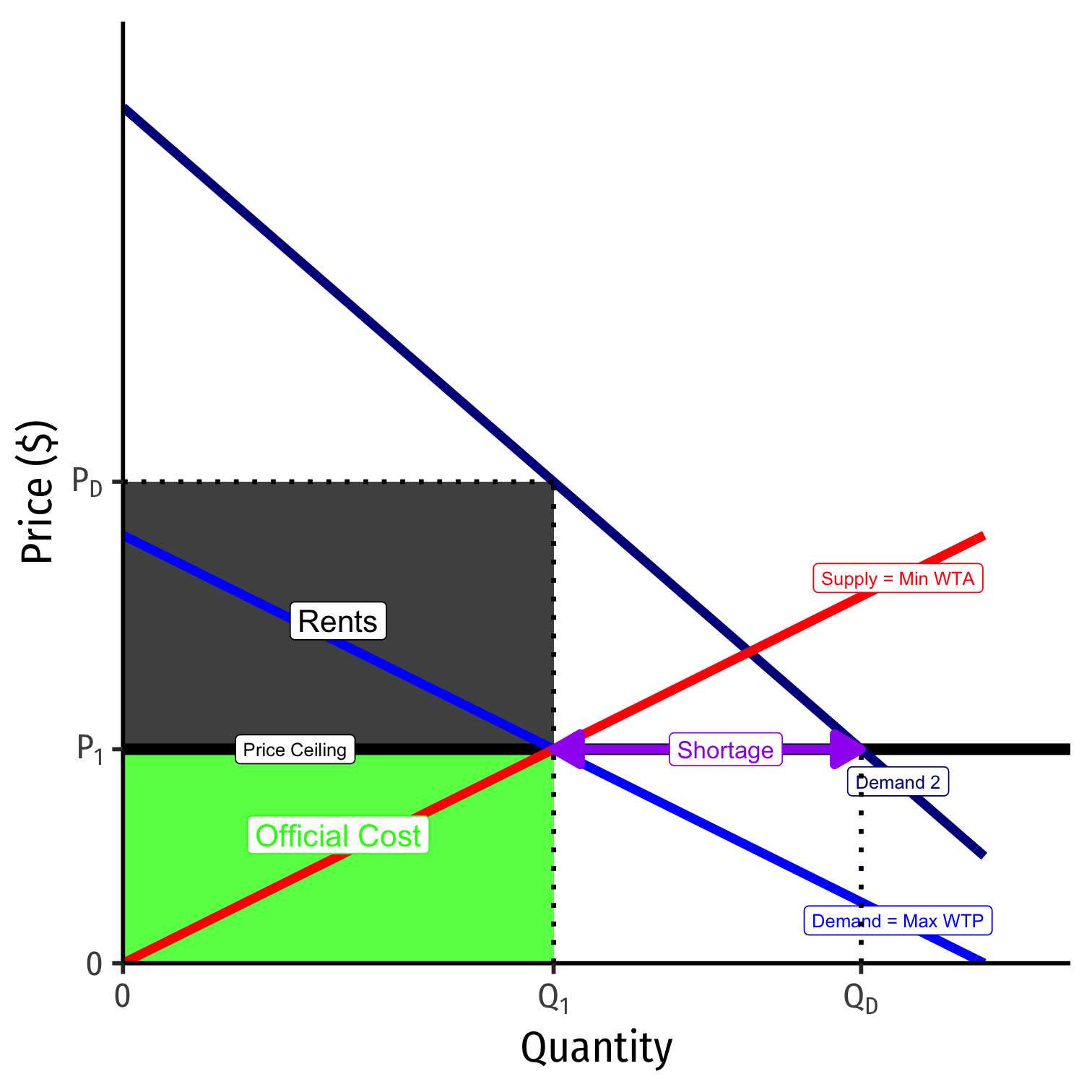

Price Gouging Laws

- Official price is ¯P1, sellers gain monetary revenues

Price Gouging Laws

Official price is ˉP, sellers gain monetary revenues

Competition exists between buyers to obtain scarce Qs goods

- Buyers willing to pay Pb unofficially

Goods are distributed by non-market means:

- Queuing

- Black markets

- Political connections, favors, corruption

Rents to those who can distribute the scarce goods

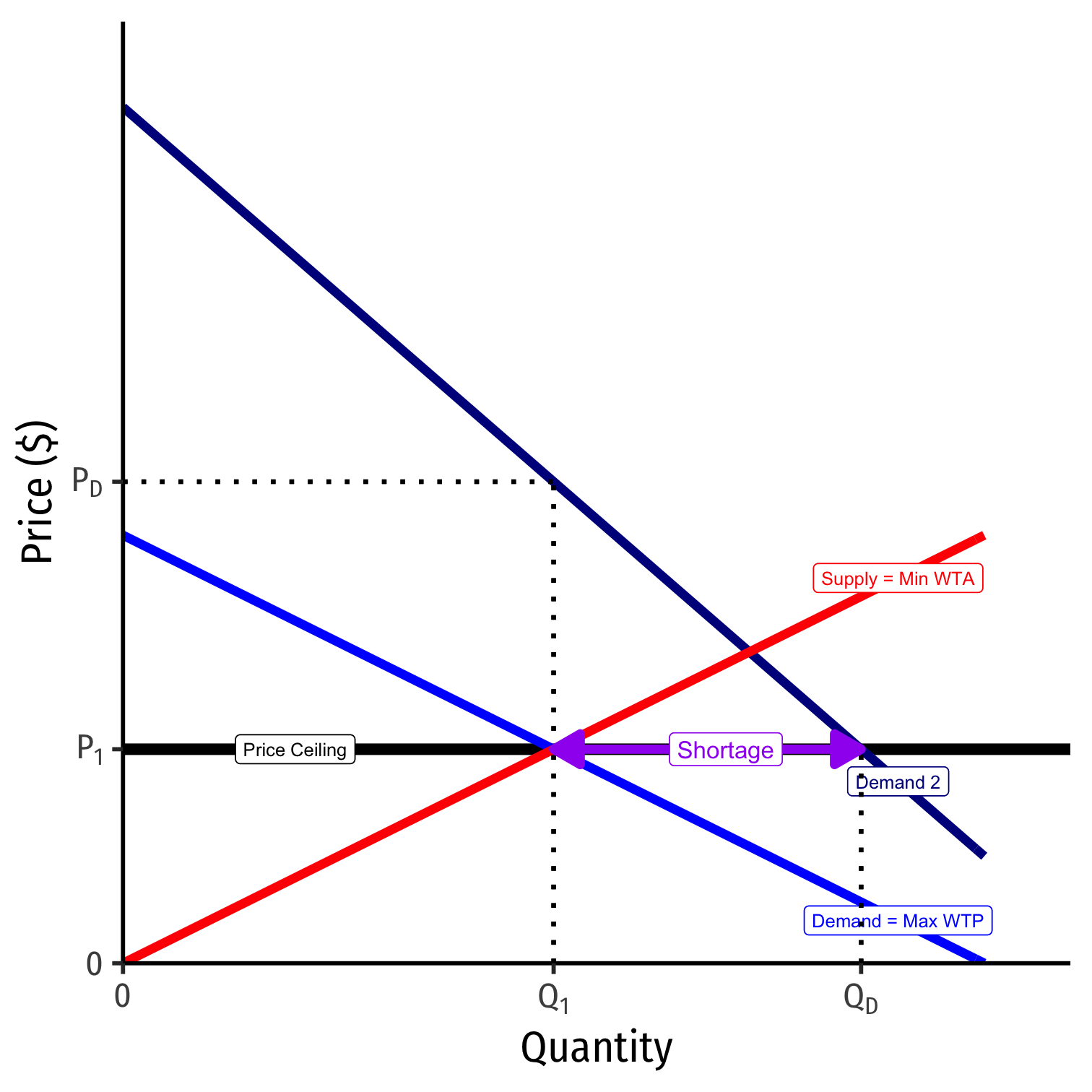

(Temporarily) Raising Prices Can Solve the Shortage

A relatively high price:

Conveys information: good is relatively scarce

Creates incentives for:

- Buyers: conserve use of this good, seek substitites

- Sellers: produce more of this good

- Entrepreneurs: find substitutes and innovations to satisfy this unmet need

(Temporarily) Raising Prices Can Solve the Shortage

"The Canadian National Post, citing the Canadian Food Inspection Agency, says that 'There are no shortages or disruptions to [food] production, importation or export,' and that 'the shelves remain stocked.' ... 'A price surge as a result of natural market forces is not something that is regulated by Canadian competition laws or otherwise. Canada’s competition laws generally don’t interfere with the free market.' ... Canadians will have enough food to eat. But it will be more expensive.

(Temporarily) Raising Prices Can Solve the Shortage

A supermarket in Denmark got tired of people hoarding hand sanitizer, so came up with their own way of stopping it.

— Birger (@Birger_s) March 18, 2020

1 bottle kr40 (€5.50)

2 bottles kr1000 (€134.00) each bottle.

Hoarding stopped!#COVID19 #Hoarding pic.twitter.com/eKTabEjScc (via @_schuermann) cc @svenseele

Forcing Low Prices Doesn't Solve the Shortage

Supply-Side Restrictions: Regulatory Burden

Supply-Side Restrictions

"As the nation’s economy and health-care system struggle to adjust to the pandemic, more and more states are reexamining some of their oldest occupational and business regulations—rules that, although couched as protecting consumers, do far more to limit competition...While some states have ordered their occupational-licensing boards to speed up the licensure of new health-care practitioners, others...are granting immediate licensing reciprocity to any practitioner licensed in any state...Even Florida, which has long jealously guarded its occupational-licensing regime to prevent semiretired snowbirds from poaching on the locals’ turf, [is] allowing out-of-state health-care providers to practice telemedicine in the state without a license."

Supply-Side Restrictions

"Also being reexamined are state certificate-of-need, or CON, laws. A product of 1970s-era economic regulation, CON laws require health-care providers to prove that new services are “needed” before they may purchase certain large equipment, open new or expanded facilities, or—as is crucial now—offer home health-care services. Often, these laws give an effective veto power to existing medical providers, allowing them to torpedo new competition for their own benefit...Basic economics predicts that competition reduces prices for consumers, and occupational licensing works directly to stifle competition."

Supply-Side Restrictions

"The University of Minnesota economist Morris Kleiner, a leading researcher on occupational licensing, estimates that licensing costs consumers nearly $200 billion annually. This might be justifiable if licensing produced substantial improvements in quality, yet most research has failed to find a connection between licensure and service quality or safety."

Supply-Side Restrictions

How did the U.S. government only manage to produce a fraction as many testing kits as its peer countries? There have been three major regulatory barriers so far to scaling up testing by public labs and private companies: 1) obtaining an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA); 2) being certified to perform high-complexity testing consistent with requirements under Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA);...

Supply-Side Restrictions

...and 3) complying with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) Privacy Rule and the Common Rule related to the protection of human research subjects. On the demand side, narrow restrictions on who qualified for testing prevented the U.S. from adequately using what capacity it did have.

Solving an Economic Crisis

An Economic Crisis

How Does a Government Respond?

- To fight normal recessions (a collapse in aggregate demand)

- Fiscal policy: lower taxes, have government spend more

- Stimulus package, bailouts, loans to businesses or individuals

- Monetary policy: lower interest rates, supply liquidity to financial markets

- Keep making it easier for businesses and individuals to borrow money

How Does a Government Respond?

- To fight negative supply shocks

- Not much one can do except ease restrictions on supply, hope for innovation

This Is Not a Normal Recession

Giving money to people does not mean they will spend it (except perhaps on necessities to survive)

- This solution assumes a normal economy with a mobile and interacting population!

Our number 1 goal should be minimize harm to individuals

- Expanded social safety nets

- Extend loans or credit to businesses