2.3: The Optimal Decision Rule

ECON 410 · Public Economics · Spring 2020

Ryan Safner

Assistant Professor of Economics

safner@hood.edu

ryansafner/metricsf19

publicS20.classes.ryansafner.com

The Story So Far

We need to create a State to constrain individuals from interfering against one another...but we also need to constrain the State

Constitutional rules define the domain of allowed collective decisions and the rules or procedures for doing so

Their practical function is to protect minorities from the majority

The Story So Far

Political rules allow us to make one collective choice for all, even though many will disagree with the outcome

We must agree at a constitutional level so that we can disagree on political outcomes

James Buchanan and Gordon Tullock

James Buchanan and Gordon Tullock

1962, The Calculus of Consent

Buchanan:

- 1986 Nobel Prize in Economics

- Collective choice as exchange, constitutional political economy, political philosophy

Tullock:

- Rent-seeking, transitional gains trap, autocracy, law & economics

Brings economic tools to political science: politics as exchange

Public Choice and Behavioral Symmetry

Behavioral Symmetry

James Buchanan and Gordon Tullock

"Political theorists seem rarely to have used this essentially economic approach to collective activity. Their analyses of collective-choice processes have more often been grounded on the implicit assumption that the representative individual seeks not to maximize his own utility, but to find the "public interest" or "common good," (p. 19)

Buchanan, James M and Gordon Tullock, 1962, The Calculus of Consent: Logical Foundations of Constitutional Democracy

What is the "Public Interest" or the "Common Good"?

Naive Political Economy

Naive Political Economy

People often recommend optimal policies that could effectively be installed by a benevolent despot who can

- Correctly identify "the public good"

- Has the desire and incentives to achieve it

- Has no constraints

Robust Political Economy

- In reality, 1st-best policies are distorted by the knowledge problem, the incentives problem, and politics

- Real world: 2nd-to-nth-best outcomes

Behavioral Symmetry

James Buchanan and Gordon Tullock

"Throughout the ages the profit-seeker, the utility-maximizer, has found few friends among the moral and the political philosophers...In the political sphere the pursuit of private gain by the individual participant has been almost universally condemned as 'evil' by moral philosophers of many shades. No one seems to have explored carefully the implicit assumption that the individual must somehow shift his psychological and moral gears when he moves between the private and the social aspects of life," (p. 19)

Buchanan, James M and Gordon Tullock, 1962, The Calculus of Consent: Logical Foundations of Constitutional Democracy

Behavioral Symmetry

James Buchanan and Gordon Tullock

"We are, therefore, placed in the somewhat singular position of having to defend the simple assumption that the same individual participatesin both processes [the market and politics] against the almost certain onslaught of the moralists," (p. 19)

Buchanan, James M and Gordon Tullock, 1962, The Calculus of Consent: Logical Foundations of Constitutional Democracy

Politics as Exchange

James Buchanan and Gordon Tullock

"The economic approach, which assumes man to be a utility-maximizer in both his market and his political activity, does not require that one individual increase his own utility at the expense of other individuals. This approach incorporates political activity as a particular form of exchange; and, as in the market relation, mutual gains to all parties are ideally expected to result from collective action," (p. 23)

Buchanan, James M and Gordon Tullock, 1962, The Calculus of Consent: Logical Foundations of Constitutional Democracy

Politics as Exchange

James Buchanan and Gordon Tullock

"The power-maximizing approach, by contrast, must interpret collective choice-making as a zero-sum game...When one man gains, the other must lose; mutual gains from "trade" are not possible in this conceptual framework," (p. 23-24)

Buchanan, James M and Gordon Tullock, 1962, The Calculus of Consent: Logical Foundations of Constitutional Democracy

Levels of Rules

The Political and the Constitutional

- We must be able to examine both levels simultaneously:

Constitutional level choice among alternative sets of rules

Political level choice within a specific set of rules

The Political and the Constitutional

Each level affects the other

Constitutional rules constrain political decisions

Current political situation (preferences, interests, wealth, power) tints how we view particular constitutional rules

How to Decide How to Decide

Veil of Uncertainty

Behind veil of uncertainty at the constitutional moment

- Rawlsian veil of ignorance

Individuals do not know if they will be in majority or minority

Need to know costs of State action, but can't know this before we know how State is organized

Collective Action on the Margin

B&T assume some pre-existing property rights at some minimal level

What further collective action will individuals agree to?

"When will a society composed of free and rational utility-maximizing individuals choose to undertake action collectively rather than privately?

- Pre-existing externalities that individuals cannot mitigate alone

Collective Action on the Margin

Pre-existing externalities that individuals cannot mitigate alone

Failing to act collectively would leave these externalities

Constitutional Political Economy

James Buchanan and Gordon Tullock

"There should be little reason to expect that constitutional rules developed in application to the passage of general legislation would provide an appropriate framework for the enactment of legislation that has differential or discriminatory impact on separate groups of citizens," (p. 22)

Buchanan, James M and Gordon Tullock, 1962, The Calculus of Consent: Logical Foundations of Constitutional Democracy

The Unanimity Rule

What is the moral status of a decision rule?

- Like "majority rule"

Unanimity is ideal: Pareto efficient by definition

Choice of constitutional rules should be unanimous, so we can disagree about political outcomes

The Unanimity Rule

But there are costs of trying to secure unanimity!

- Need everyone to agree

A less-than-unanimous rule will create other costs on minorities that are not in the majority

Consider two types of costs to determine optimal departure from unanimity

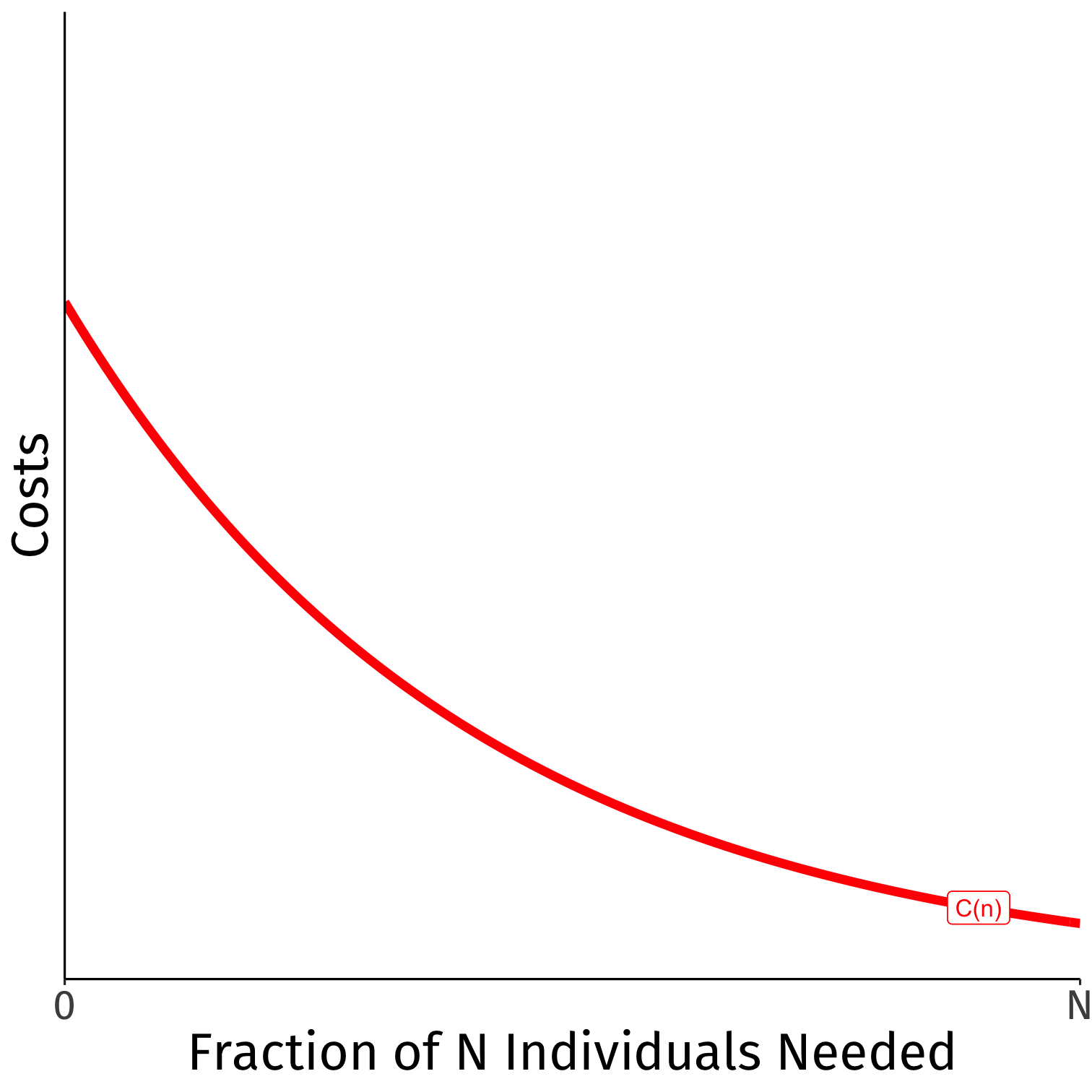

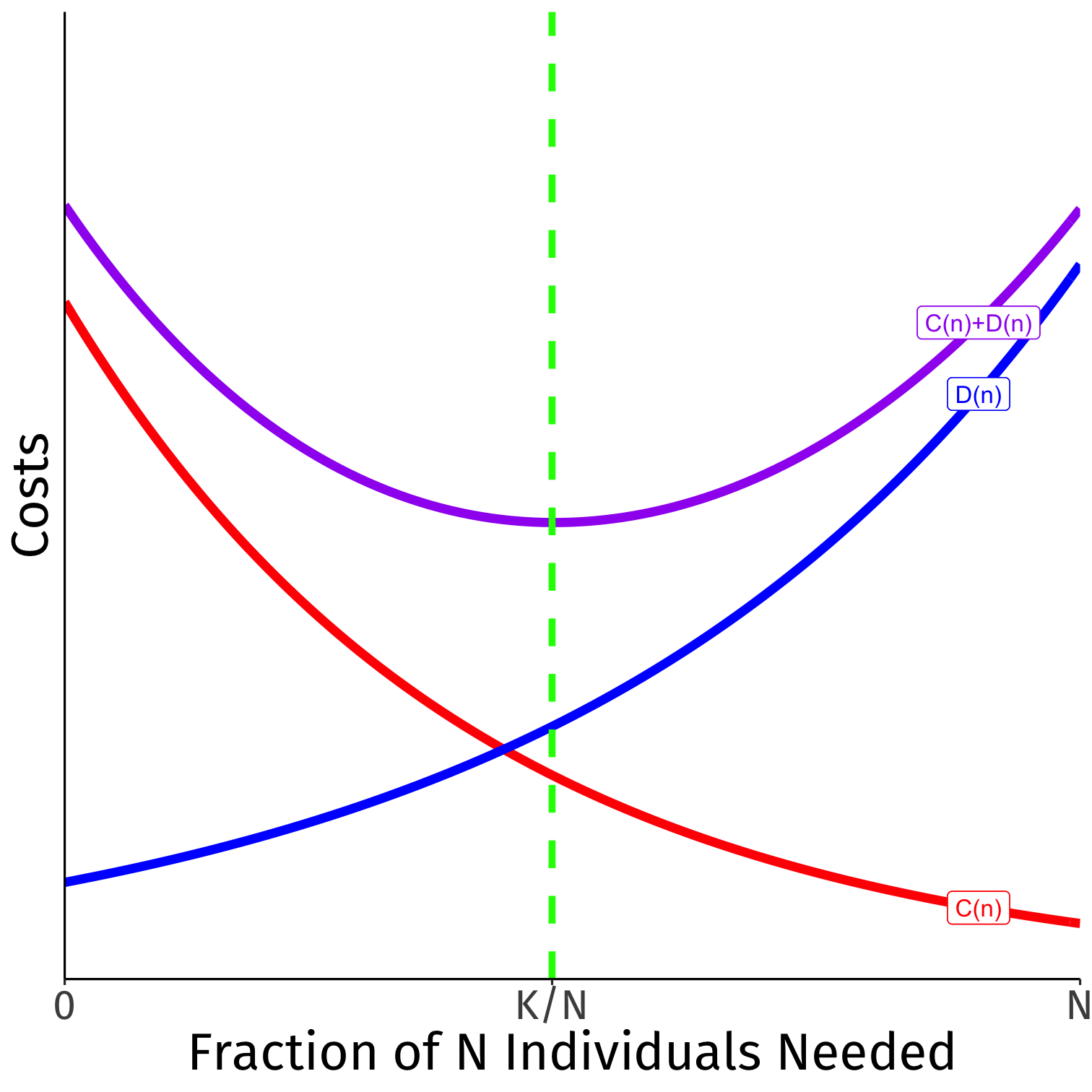

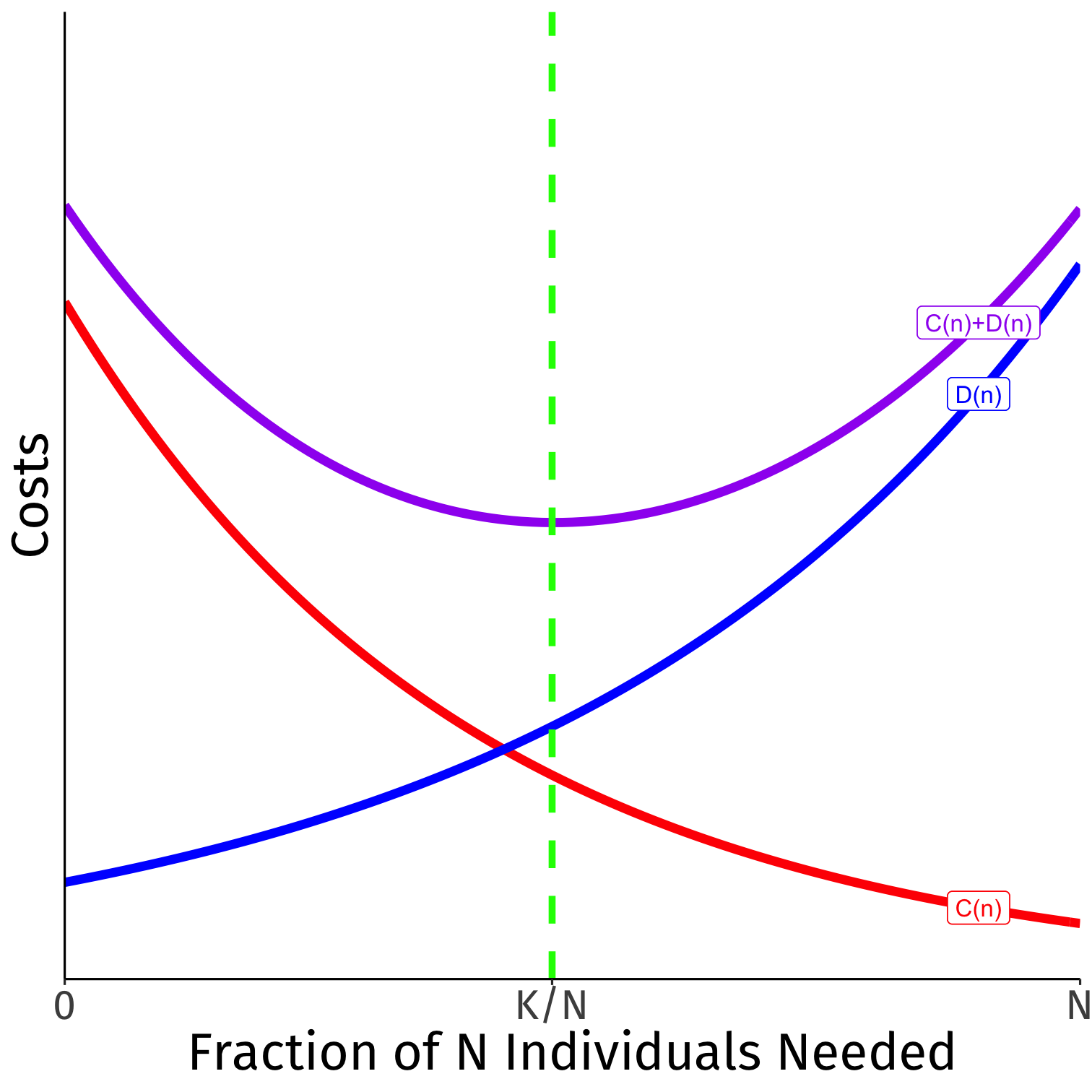

External Costs

External costs, \(C(n)\): cost of collectively-chosen outcome on individual

Fall with \(n\)

Expected cost of being in minority and coerced to comply with unfavorable decision

Some expected cost at 0, personal cost of unresolved externality

With unanimity \((N)\), external costs \(\rightarrow 0\)!

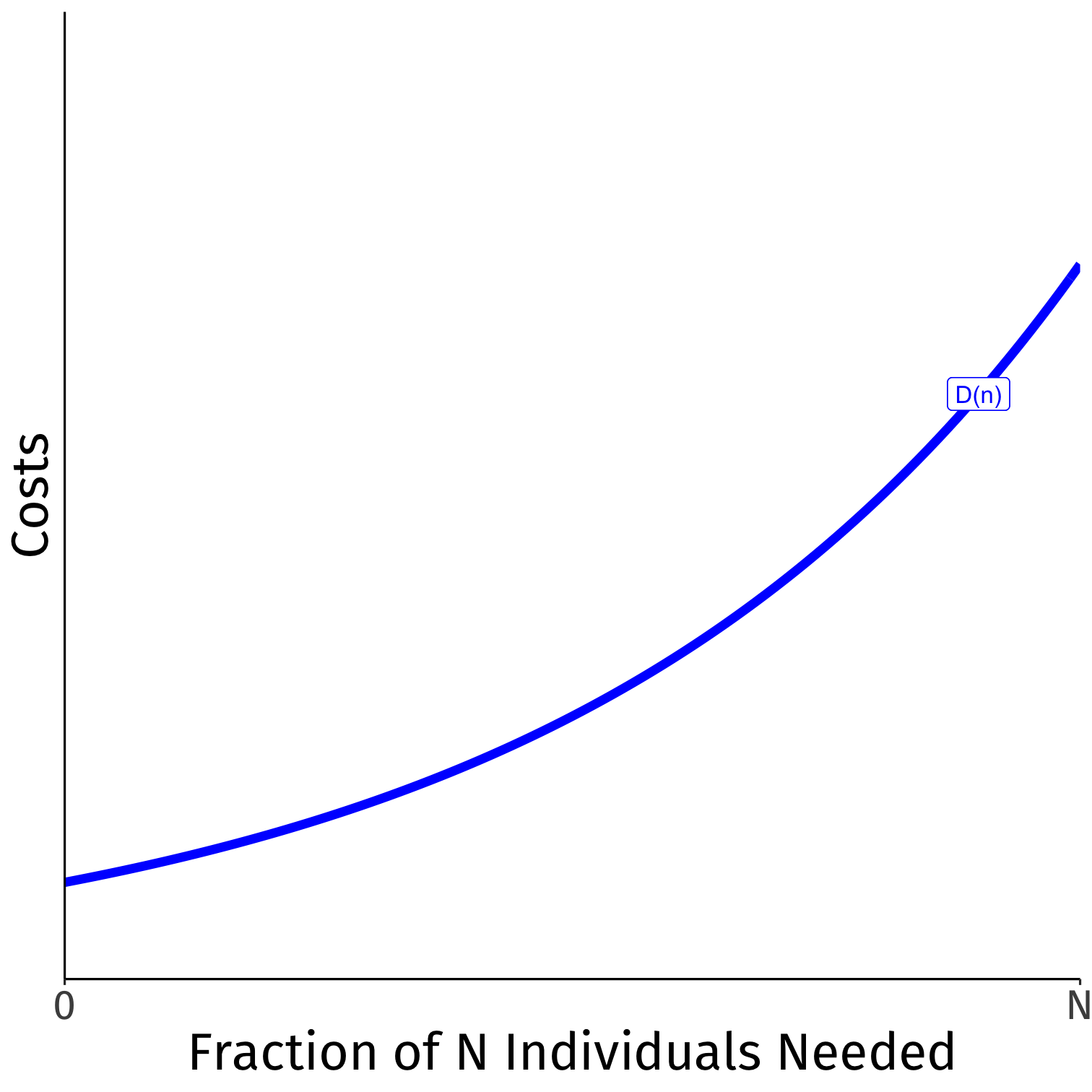

Decision-making Costs

Decision-making costs, \(D(n)\): cost of reaching an agreement

Increase exponentially with \(n\)

With more people, any one person can veto!

Holdouts, strategic bargaining, high transaction costs

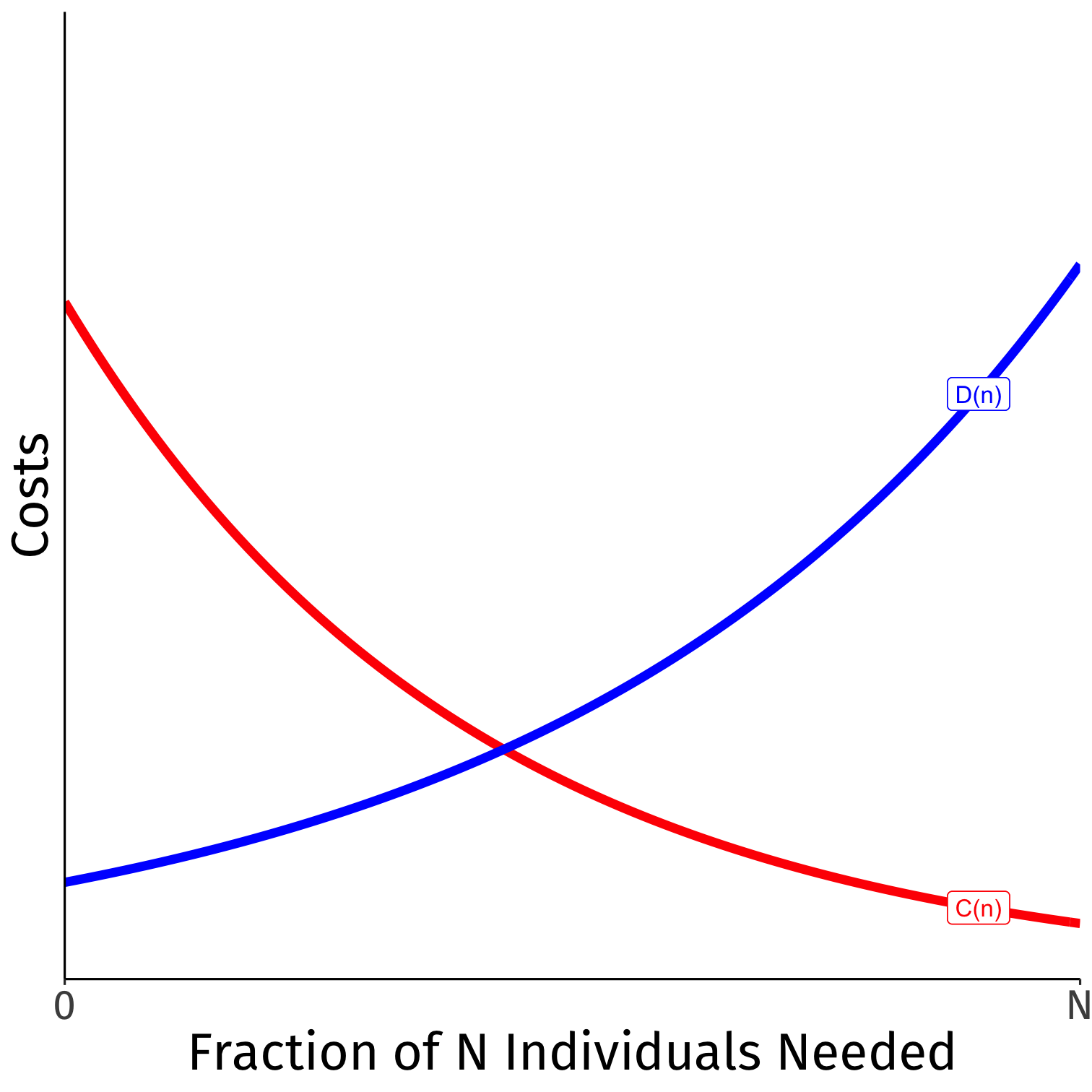

Optimal-Decision Rule

- With greater \(n\), a tradeoff between lower External costs \(C(n)\) and higher Decision-making costs \(D(n)\)

Optimal-Decision Rule

With greater \(n\), a tradeoff between lower External costs \(C(n)\) and higher Decision-making costs \(D(n)\)

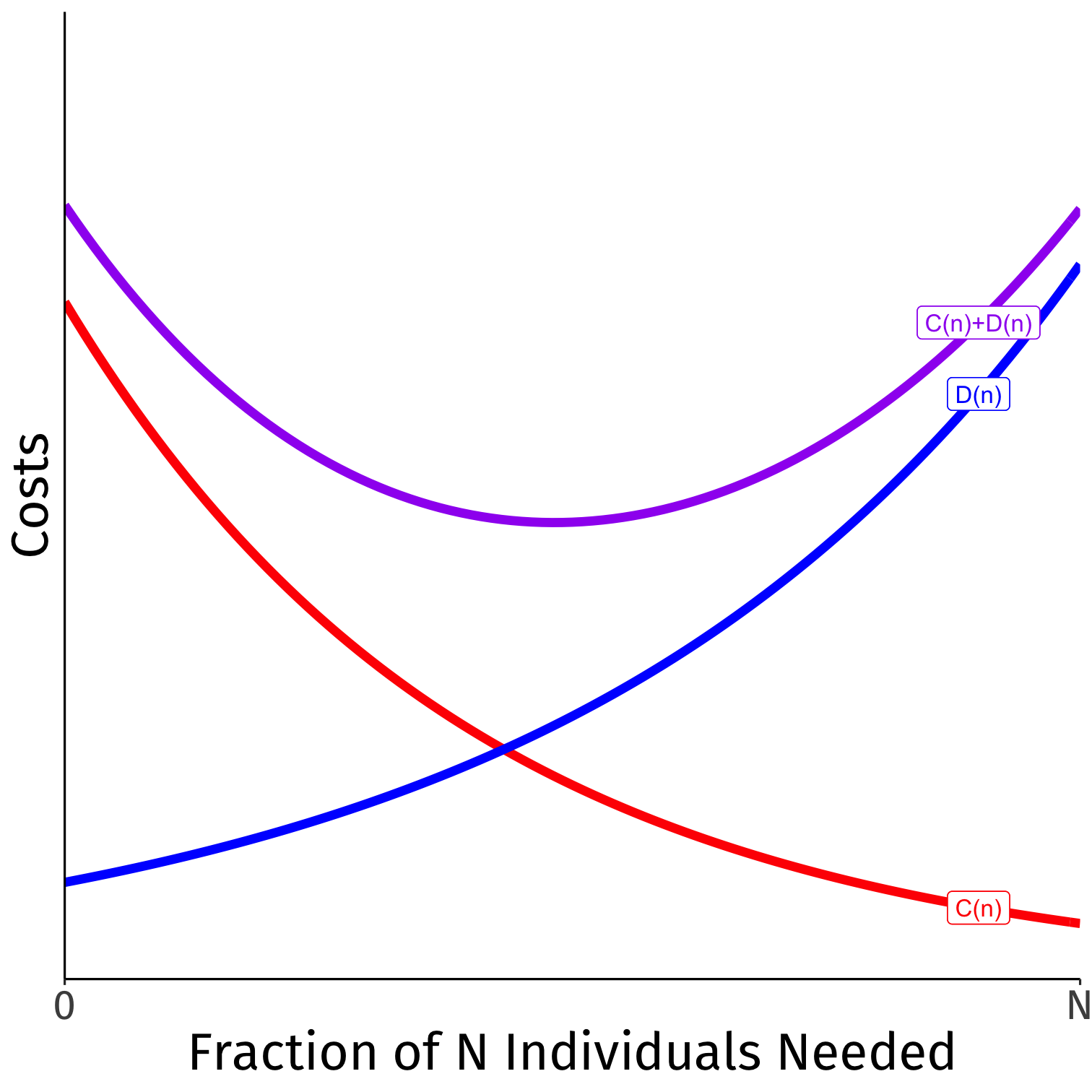

Total costs \(C(n)+D(n)\): the (vertical) sum of external and decision-making costs

Optimal-Decision Rule

With greater \(n\), a tradeoff between lower External costs \(C(n)\) and higher Decision-making costs \(D(n)\)

Total costs \(C(n)+D(n)\): the (vertical) sum of external and decision-making costs

Optimal decision rule: minimize total costs at \(\frac{K}{N}\)

Optimal-Decision Rule

ANY group of \(\frac{K}{N}\) people that agree will determine the outcome

- "the decisive set"

Note: again, the minimum of Total Costs

- not necessarily the intersection of External costs and Decision-making costs

- not necessarily a simple majority \(\frac{n}{2}+1\)!

The Benefits of Majority Rule

Majority rule \(\left(\frac{n}{2}+1\right)\) is a very common decision rule

Despite moral arguments for/against, practical reasons:

- It's the smallest possible group which can ensure there will not be two contradictory measures passed

- Can break a "voting cycle" (next class!)

Optimal Decision Rules Vary

Costs are different issue by issue

- No single voting rule optimal for all issues

High \(C(n)\)-issues

- Exercise of State power vs. individual

- Constitutional amendment

- Criminal convictions

- Much more than a majority

Optimal Decision Rules Vary

Costs are different issue by issue

- No single voting rule optimal for all issues

High \(C(n)\)-issues

- Exercise of State power vs. individual

- Constitutional amendment

- Criminal convictions

- Much more than a majority

Optimal Decision Rules Vary

- Low \(C(n)\)-issues, common access rules:

- Nomination (1 person)

- Introducing a motion/bill (moved and seconded)

- Writ of certorari

- Much less than a majority

Common Decision Rules

Access rules: less than majority

- Bringing issues to the group

Decision rules: majority

- Actual business of passing resolutions

Changing the rules: more than majority (closer to unanimity)

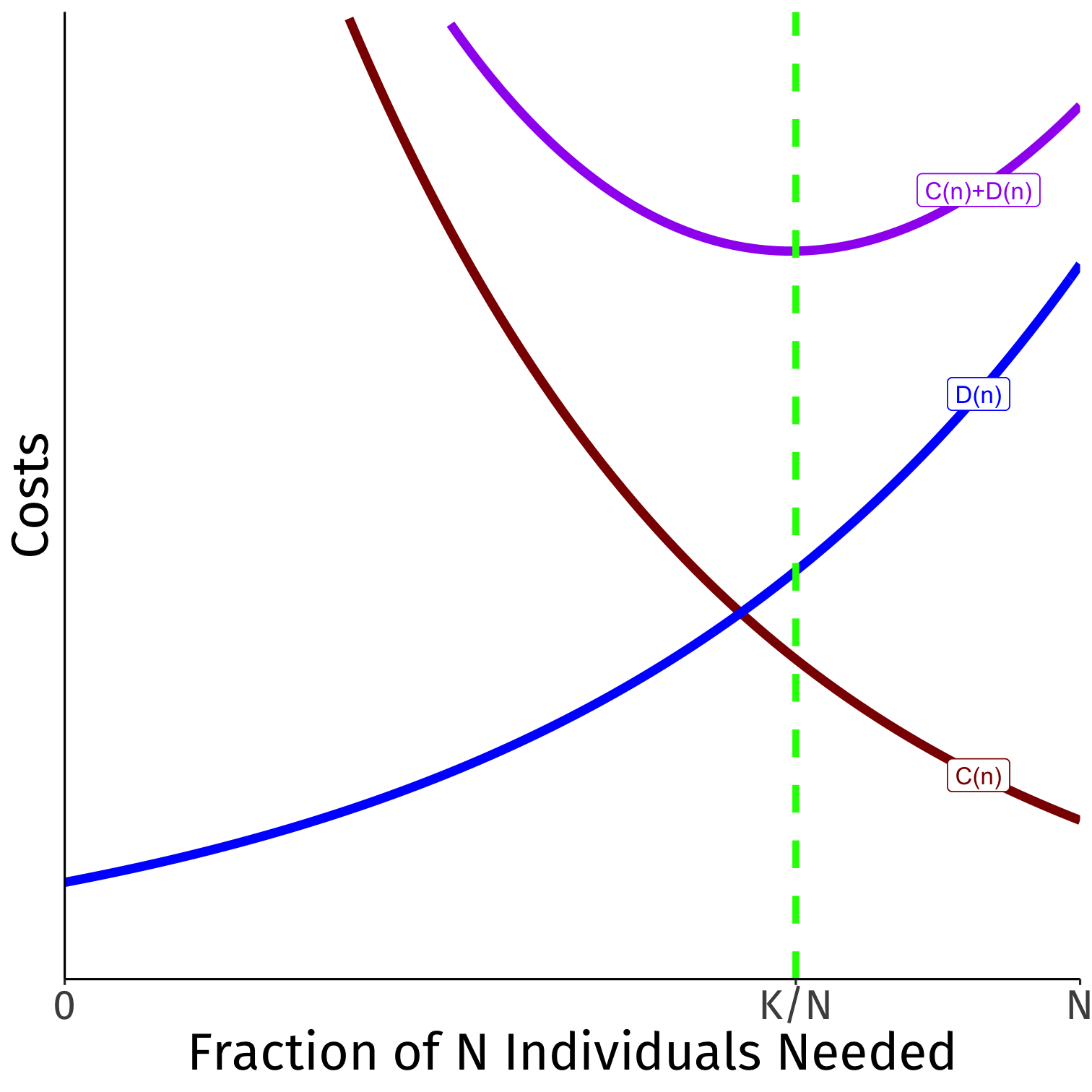

What Affects Total Costs

Size of \(N\): larger groups create larger \(C+D\) costs

- We want the smallest group consistent with the size of the externality

Heterogeneity (of preferences, wealth, power, etc)

- \(C\)-costs rise: greater fear of being in minority

- \(D\)-costs rise: harder to get very different people to agree

Heterogeneity

James Buchanan and Gordon Tullock

"Many activities that may be quite rationally collectivized in Sweden, a country with a relatively homogenous population, should be privately organized in India, Switzerland, or the United States."

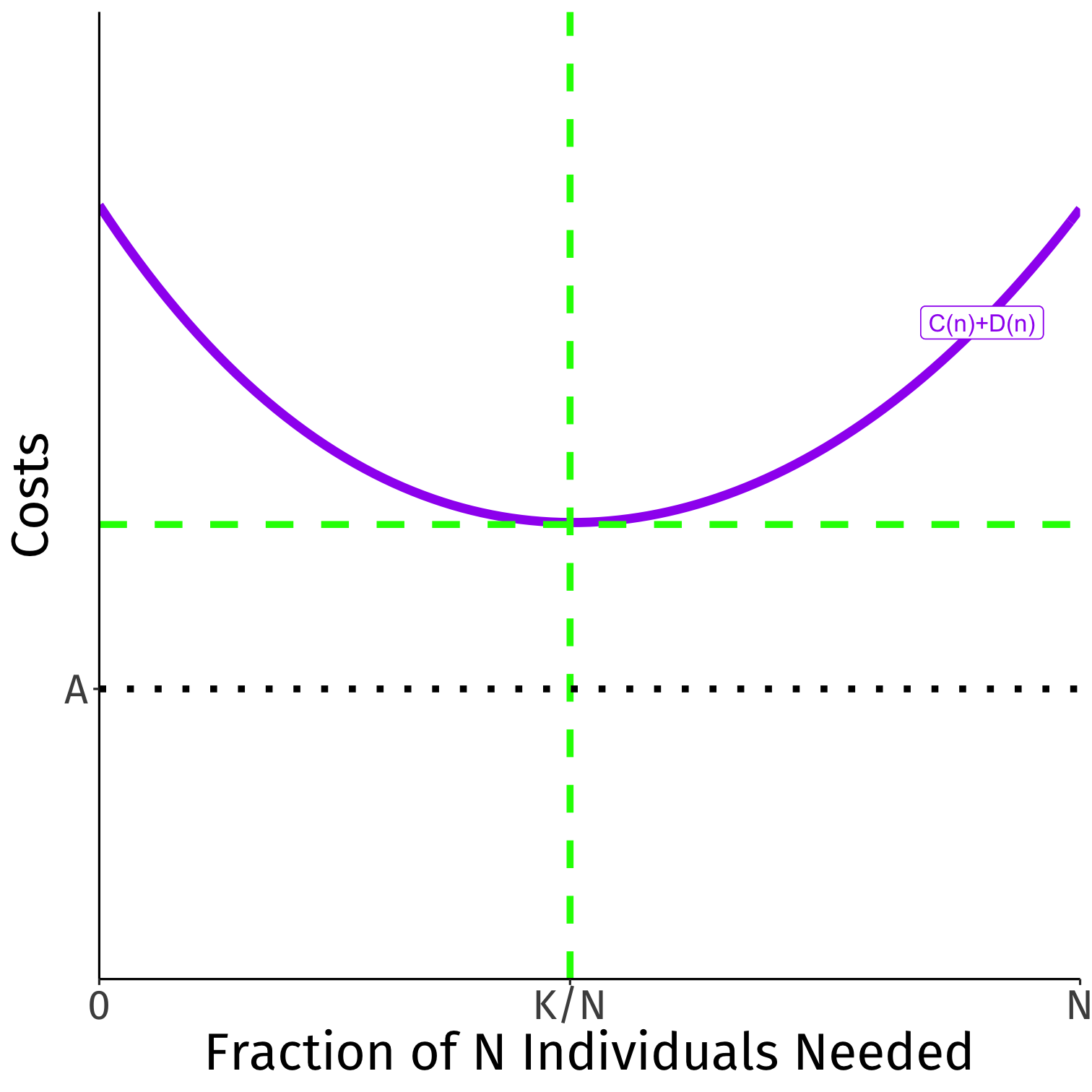

Comparing the Cure and the Disease

Different alternative decisions regarding an externality have different costs:

\(A\): do nothing, live with externality

\(B\): voluntary collective action

- cost of collective action might yield underprovision

\(C\): government action

- cost of collective action might create new political externalities

Comparing the Cure and the Disease

James Buchanan and Gordon Tullock

"The existence of external effects of private behavior is neither a necessary nor a sufficient condition for an activity to be placed in the realm of collective choice," (p.61)

Buchanan, James M and Gordon Tullock, 1962, The Calculus of Consent: Logical Foundations of Constitutional Democracy

When Optimal Collective Action is Second-Best

Even with optimal collective decision rule, it might be better off left to private hands if total costs are lower (at A)

In general, the higher \(C+D\) costs are (for whatever reason), the greater likelihood that an activity should be left private

The Importance of the Starting Point

Constitutional choice does not take place in a vacuum

Veil of ignorance assumes we have no specific stake in changing rules in a particular way, but

Our current political situation (preferences, wealth, power, etc.) naturally will affect how we view different rules

The Importance of the Starting Point

Incorrect to start from Hobbes (no rules); irrelevant to our actual decisions

Constitutional economics is practically about reform of rules, rather than designing from scratch

We must always start from where we are

We would build a different house from scratch than if we change our existing one